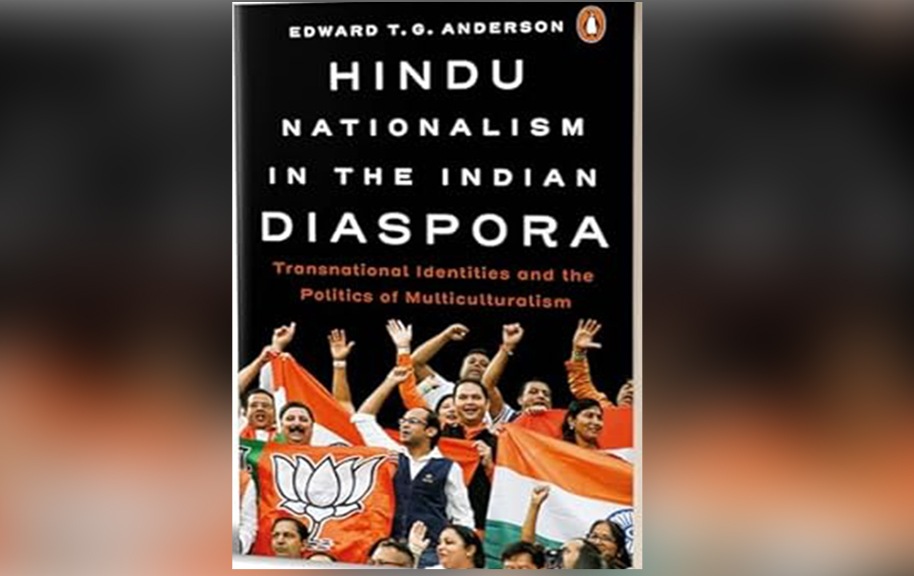

Book Review: Hindu Nationalism in the Indian Diaspora by Edward Anderson

Updated: December 14, 2024 2:22

A little knowledge is a dangerous thing. And this gets aptly reflected in the work of a number of academicians from the western world who have produced half-baked and biased research work on Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). The latest to enter this stable is Edward Anderson with his recently released work ‘Hindu Nationalism in the Indian Diaspora’.

The book primarily focuses on the work of Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS) in Britain. Anderson’s work is full of factual errors and reflects his anti-RSS bias emerging out of preconceived notions.

There are two basic premises that are the foundation of Andreson’s book. First, RSS has transplanted Hindutva through HSS in a planned manner in various countries including Britain. The fact of the matter is that wherever RSS volunteers went, they started organisations like HSS to remain connected with their cultural roots and to do service work for the society. It witnessed organic growth.

Interestingly while in the first 60 pages of this book, Anderson rejects the idea of organic growth and talks in detail about how well-oiled the RSS machinery is and how it is uses its daily shakha as a primary tool for building a strong network that has become very influential in several countries including Britain, then he contradicts himself (pp63) as he takes an about turn, “But it must be noted that the image of the Sangh as a well-oiled, entirely synchronised movement has clear propaganda purposes; in actual fact Shakhas can be rather more haphazard and less coordinated than often presented. Attendance can be patchy and discipline not always maintained in ways that might be expected or desired.” The writer also fails to produce evidence that on what ground he has made this statement. Also, those who have watched and tracked RSS closely also know that the most important aspect of Sangh has been its meticulousness and discipline. Even the severest critics of the Sangh also admit that the Sangh work is anything but haphazard.

Anderson doesn’t have a basic understanding about the RSS Shakha and how it works and hence he falters gravely on facts. He explained the Shakhas in India and diaspora with a fundamental inaccuracy. Anderson writes, “Although they vary(swayamsevaks) in age, there is an emphasis on young men. In the diaspora mixed age specialisation is striking, although shakha subdivides into different age groups for certain activities…there are proportionately fewer older swayamsevaks ..The relatively smaller number of older swayamsevaks is due to high dropout rate-games and peer socialisation elements appeal more to younger members.”

This statement is factually incorrect. The writer is perhaps not aware that the RSS has different shakhas for different age groups. Especially for the older ones there are separate Shakhas. These are called ‘Praud Shakhas’(Shakhas for the elderly one). And these Shakhas see the largest number of elderly people.” There is no data-based evidence available on the basis of which Anderson is talking about the number of attendees in the Shakhas as there is no formal membership in the RSS and hence there is no record. The HSS gatherings are also informal and attending a Shakha there doesn’t involve any membership. So, on which basis, the author is making such random guesses?

Anderson is also absolutely off the mark when he writes on Emergency (1975-77) and the role of RSS and diaspora Hindus. He seems to have ignored the reporting by Foreign Press that clearly established in its reportage that the RSS and Bharatiya Jana Sangh(BJS) led from the front the movement to fight against Emergency and restore democracy in India. In fact, Anderson tries to give complete credit for this movement to the non-Congress left whereas it is well-known that a large section of the left had joined hands with Congress.

Here also Anderson contradicts himself as he says Emergency provided an opportunity for mainstreaming of Hindu nationalism as it allowed “BJS to enter mainstream politics through its role in the anti-emergency coalition.” He also adds(pp.126), “One of the most important outcomes of the Emergency was its impact on the political success of the Hindu right.” The question that Anderson needs to answer is that if the RSS had done nothing much in Emergency, then why and how did it create so much impact that ‘Hindu nationalism’ was mainstreamed?

Anderson seems to have no clue about the relationship between the RSS and its inspired organisations and how it works. He makes laughable assertions (of course without evidence again) such as(pp.163) “..Disagreements (over approach more than ideology) that the VHP had with the RSS and the BJP have caused tension and even acrimony.”

The second fundamental premise that formed the basis of this book makes the bias of the author very clear. It also reflects his lack of understanding about the difference between the Western Nationalism and Hindu Nationalism. Anderson’s premise perpetuates the stereotype image of Hindus, Hindu nationalism and the RSS as he begins his book with this premises, “Hindu nationalism is a majoritarian, conservative, and militant political ideology and ethno-religious movement that rejects pluralistic secularism and is ascendent in contemporary India.” Significantly, to support his arguments, most of which are without evidence or based on wrong notions, Anderson has largely quoted all those anti-RSS authors who are notoriously known for producing books like this with regular frequency. The body of work which gives factual information about the RSS is rejected by these authors as hagiographies. In a nutshell, Anderson’s book is yet another primer from the stable of RSS baiters on how to write a ‘political pamphlet’ against RSS and Hindu nationalism.

(The article was first published in moneycontrol.com. Link: https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/opinion/misinformed-narrative-edward-anderson-s-book-a-flawed-primer-on-hindu-nationalism-and-rss-12889158.html )